|

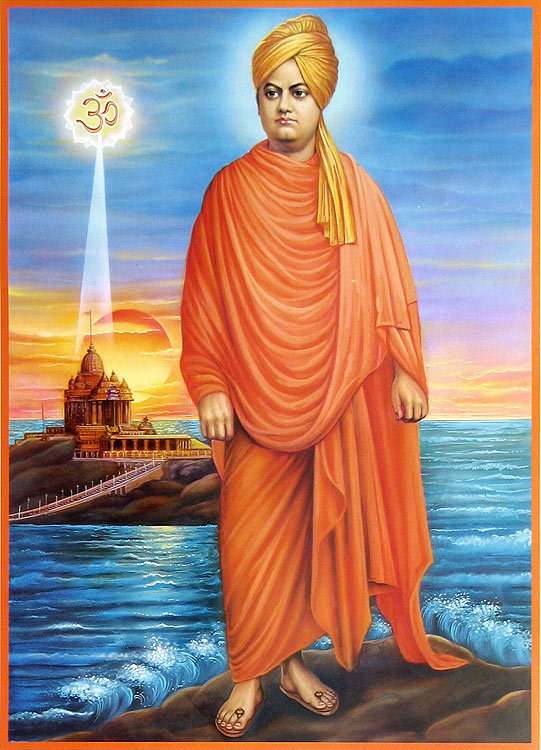

Swami Vivekananda:

In 1897 Swami Vivekanda arrived in America as an anonymous and penniless sannyasin (wandering monk). He had travelled to America as a representative of Hinduism and the ancient Indian tradition of Vedanta. Yet Vivekananda was not bound by any formal ties of religion.

To the World Parliament of Religions he offered a message of a shared spirituality and the harmony of world religions. This universal message and his dynamic spiritual personality won the hearts and minds of many seekers; and his vision is still treasured today.

“Arise! Awake! And stop not till the goal is reached.”

Early Life of Vivekananda |

Vivekananda particularly liked the rational reasoning of the West and was easily dismayed by many of the religious superstitions and the cultural decline that Indian society found itself in. Thus Vivekananda was drawn to join the Brahmo Samaj. The Brahmo Samaj was a modern Hindu movement who sought to revitalise Indian life and spirituality through a rationalistic approach and abandonment of image worship.

This included the great Devendranath Tagore (father of Rabintranath Tagore) However Devendranath told Vivekananda that he saw in him the eyes of a Yogi and surely he would realised god in this lifetime. Although none could satisfy his question, he came to hear of the name Ramakrishna Paramahamsa who was reputed to be a great Spiritual Personality and had realised god

|

|

|

Ramakrishna - Vivekananda

In many ways Ramakrishna was different to Vivekananda. Ramakrishna was an illiterate and simple villager who had taken a post at a local Kali temple. However his simple exterior hid a personality of extraordinary spirituality.

For many years Ramakrishna had pursued the most intense spiritual practices burning with a longing for realisation of his beloved Mother Kali But after attaining realisation, Ramakrishna not only practised Hindu rituals, but also pursued the spiritual paths of all the main religions.

Sri Ramakrishna came to the conclusion that all religions lead to the same goal of union with the infinite. It was thus fitting that his closest disciple, Vivekananda would later eloquently spread this message, - the harmony of world religions. As Sri Arbindho would later say:

|

Ramakrishna instantly recognised the spiritual potential of Vivekananda and lavished attention on Vivekananda, who at first did not always appreciate this. In the beginning the reasoning mind of Vivekananda was sceptical of this God intoxicated Saint and Vivekananda would frequently question and debate his teachings. However, slowly the spiritual magnetism of Sri Ramakrishna melted Vivekananda’s heart and he began to experience the real spirituality that Ramakrishna exuded. Thus Vivekananda mental opposition faded away to be replaced by an intense surrender to the Divine Mother and a burning longing for realisation.

However for Vivekananda, personal liberation was not enough. His heart ached for the downtrodden masses of India who suffered poverty and many hardships. Vivekananda felt that the highest ideal was to serve God through serving humanity. Thus Vivekananda would later add social work as an important element of the Ramakrishna order. Thus after spending a few years in meditation Vivekananda became restless and began travelling throughout India, visiting many of the holy sites.

After travelling through India and coming into contact with many influential figures, it was suggested that Vivekananda would make an ideal candidate to represent Hinduism at the World Parliament of Religions which was shortly to be held in Chicago, USA. Before leaving Vivekananda went to receive the blessings of Saradha Devi, the wife of Sri Ramakrishna. After receiving her encouragement and blessings he made the momentous journey to America dressed in his ochre robe and maintaining the vows of a Sanyasin |

|

Vivekananda – World Parliament of Religions

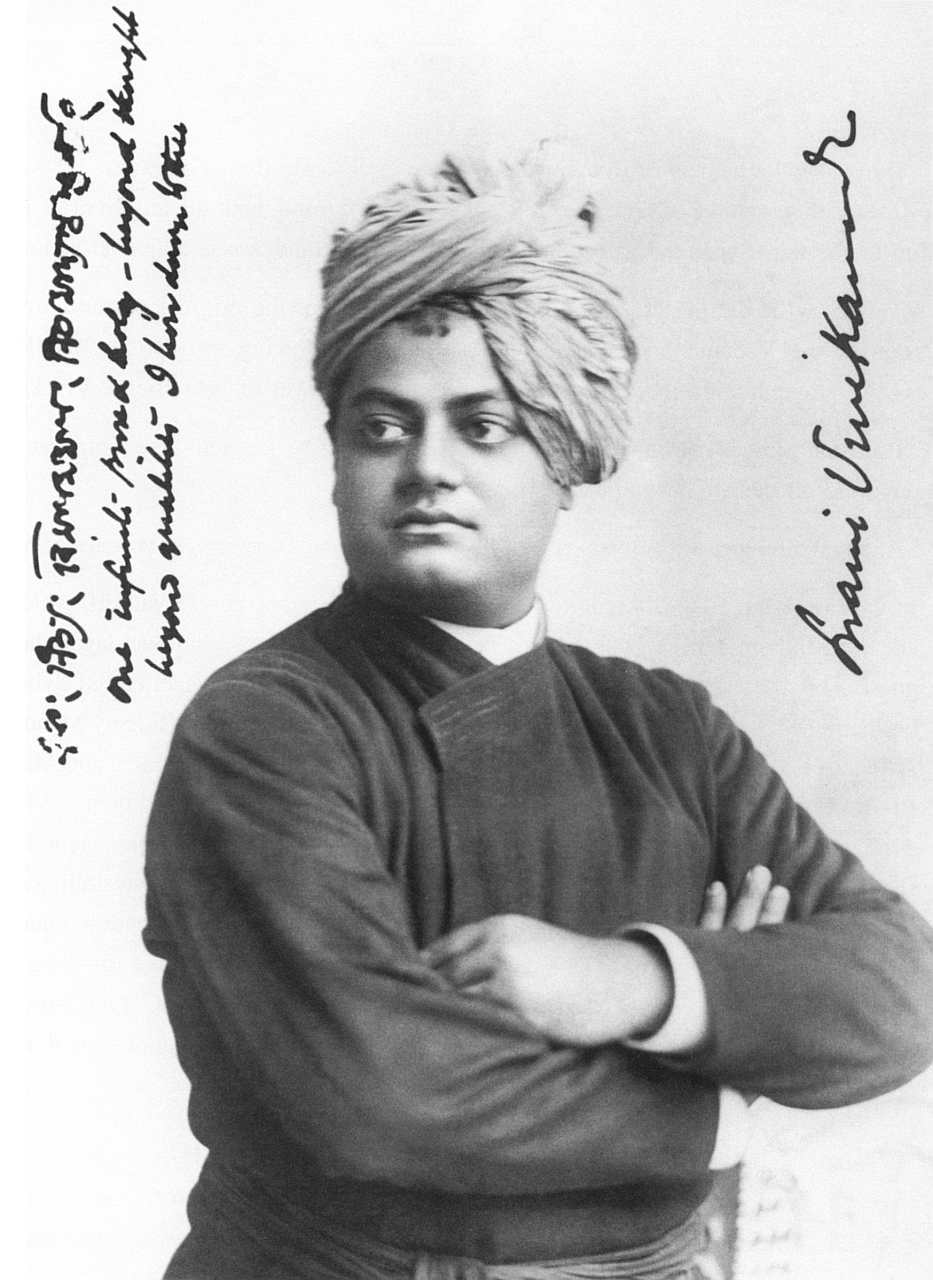

Vivekananda at the Parliament of World Religions

Vivekananda passed away at the young age of 39 but he achieved a remarkable amount in this short time on earth. He combined the ancient spiritual traditions of India with the dynamism of the West. Many Indian politicians would later offer their gratitude to the impact and ideals of Vivekananda. To many Vivekananda is regarded as the patron saint of modern India.

|

|

Cause of Swami Vivekananda’s death:

Written when he was travelling in Kashmir with some disciples, including some American and English disciples—it was read aloud at breakfast that early morning.

The poem was preserved by one of his American disciples, Mrs. Ole Bull. While it may have been a coincidence and possibly not unique that someone wrote a poem in praise of the day/holiday on which he happened later to die, it may be singular that it was written by someone whose death has been much debated as to its cause (and for reasons other than this poem).

|

|

|

The Swami passed away at the age of thirty-nine years, five months and twenty-four days, thus fulfilling a prophecy which was frequently on his lips, “I shall never live to see forty.”

|

Once in Kashmir, after an attack of illness, I had seen him lift a couple of pebbles, saying, “Whenever death approaches me, all weakness vanishes. I have neither fear, nor doubt, nor thought of the external. I simply busy myself making ready to die. I am as hard as that” — and the stones struck one another in his hand — “for I have touched the Feet of God!”

Descending the stairs of the shrine, he walked back and forth in the courtyard of the monastery, his mind withdrawn. Suddenly the tenseness of his thought expressed itself in a whisper loud enough to be heard by Swami Premananda who was nearby. The Swami was saying to himself, “If there were another Vivekananda, he would have understood what Vivekananda has done! And yet, how many Vivekanandas shall be born in time!!” This remark startled his brother-disciple, for never did the Swami speak thus, save when the flood-gates of his soul were thrown open and the living waters of the highest Consciousness rushed forth.

|

|